Yesterday, I suggested that I had decided not to do a selection experiment after all–I felt the plants were too far along, I was lazy, etc. Mostly, I was lazy. Hedi from the Fastplant program must have sensed this reticence on my part because later in the afternoon she sent out a post to the folks on the Fastplant network to be sure and check out a certain blog that was describing trichome selection. With her deft and well timed announcement she was able to convince me that counting trichomes was just the thing I wanted to do for the evening. 😉

So after a nice dinner out with my wife Carol, I moseyed up to the lab and counted trichomes—almost as effective as counting sheep, btw.

I suspect you can see the trichomes on this image.

It has seemed to me during this round of growing Fastplants that this particular population was a bit more hairy than others I have worked with in the past (at least before selection). The first thing I had to do was to make a decision on just what to count. Really, no one wants to count all the trichomes on a plant, especially a hairy one. What to count as a sample would determine what time I got to bed–which is an important consideration for me, but not one usually encountered in the classroom. However, in my experience, high school student’s attention span/tolerance for engrossing activities like counting hairs on little green plants is very, very small. In fact, I imagine their maximum tolerance time is about the same time as required to read this sentence. Paul W. often suggests the hairs along the first true leaf’s margin. I have tried that in the past but one thing you have to know. The plants do not exhibit a uniform hair distribution. The stem may be very hairy with hardly any on the leaf. I just had too hard of time giving up on the hairy stems. The first plant I looked at had a single hair along the leaf margin but the stem and petioles were relatively hairy. I ended up choosing counting the hairs on the first true leaf’s petiole. Sounds good but this has its own set of issues. For instance some plants have leaves without petioles (not common) while for others it is very difficult to determine what is the first true leaf. Such are some of the issues with making this type of decision. Still, the original write up for this procedure that saw, from Bruce Fell at the University of Minnesota suggested petiole. That is what I decided to count. (Also, this is suggested in the AP Biology Lab manual.)

Next I had to decide how I was going to keep track of the counts. I took some plastic plant labels and cut them up into smaller pieces so that I could label each individual plant.

I then rounded up my notebook, a pencil (waterproof), and a plastic magnifier. One thing I have found is that counting these little hairs goes better with a magnifier—that works for all ages.

Yes, I know, this looks staged since I seem to not be looking through the magnifier—actually there is a smaller lens below the bigger lens that I’m using. The modular plant growing system makes counting the hairs on the individual plants much easier than some other systems I have used.

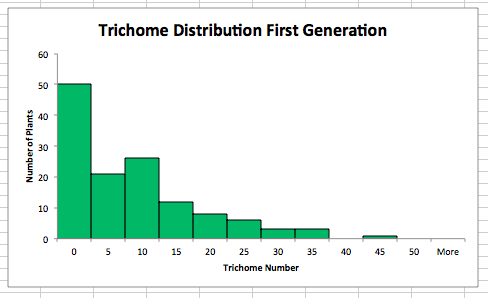

It turns out I had exactly 100 plants and my first impression about their hairiness may have been correct. Normally, the first generation (depending on the strain) has a highly skewed distribution of plants hair variation. In fact we usually get a lot of plants with zero hairs which can really present a challenge for appropriate or accepted analysis techniques. Here’s what I’m used to getting from students for the first generation.

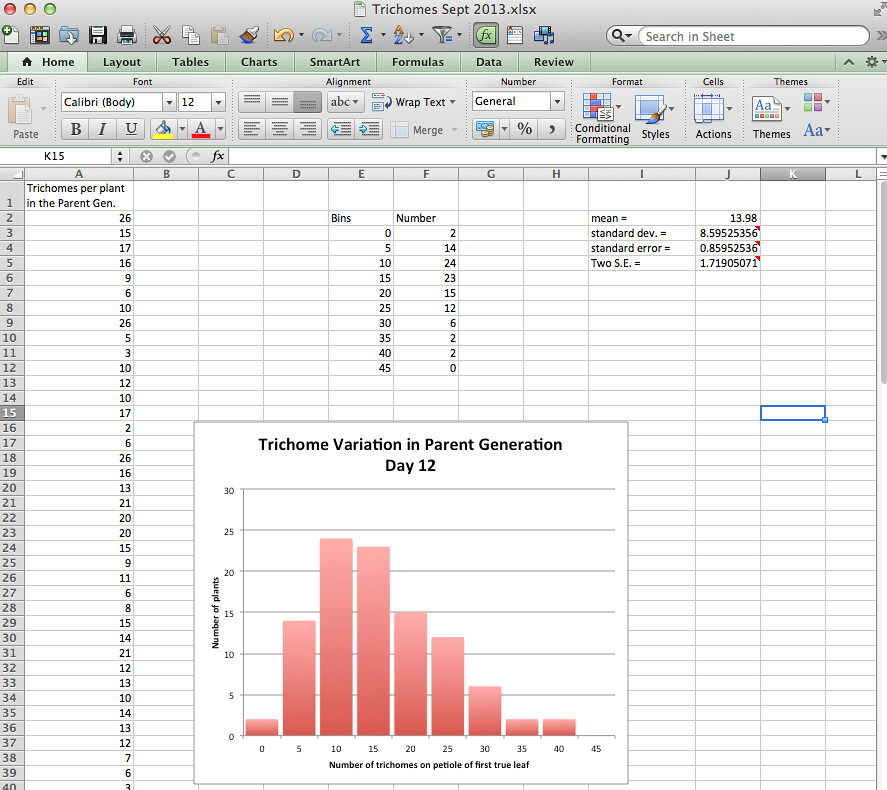

But here is what I got last night.

Based on this data, I will select all the plants with 30 or more hairs (probably along with a couple of the plants in the high twenties) and isolate them later this evening from the rest of the plants. I will create two beesticks for pollination–one for the selected population and one for the remaining plants in the population. Pollination starts tomorrow and will continue into the first of next week.

Thanks to Hedi for inspiring me to get to work.