About fifty years ago, I picked up a paperback book at the University of Kansas Student Union Oread Bookstore titled, A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold. Despite my great love for hunting, fishing, archery, camping, and hiking, I had always considered my passion for nature and the outdoors as something that was more of an avocation or hobby and had never considered pursuing biology as a career. Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac changed that perception forever.

Bookstores during this time were filled with various environmental or nature-themed books. This was the height of the back to land, environmental movement. I read most of these books but this one book stood apart. For me, Leopold helped to put words to thoughts I had had and to thoughts on the natural world and my role in that world that were just beginning to percolate. Reading this book was like becoming a member of the Leopold family. Likely, this was an easy transition because to my mind my upbringing seemed to be very much in synch with the Leopold’s. Finding Sand County Almanac was like finding an uncle I didn’t know about but who shared the same interests in nature that I had and who was willing to teach me. All of Leopold’s essays challenged my thinking, resonating deep in my subconscious. Each essay started with very familiar scenes that established emotional connections that then moved to deeper insights and unforeseen truths. Each exuded wisdom with subtle and well chosen, poetic prose. Sometimes this wisdom and these unforseen truths were intense and immediate. Essays such as “The Good Oak” or “Sky Dance” permanently changed how I harvested wood and welcomed the spring. Other essays took a while to simmer before their beauty and wisdom manifested. One such essay was “Draba”.

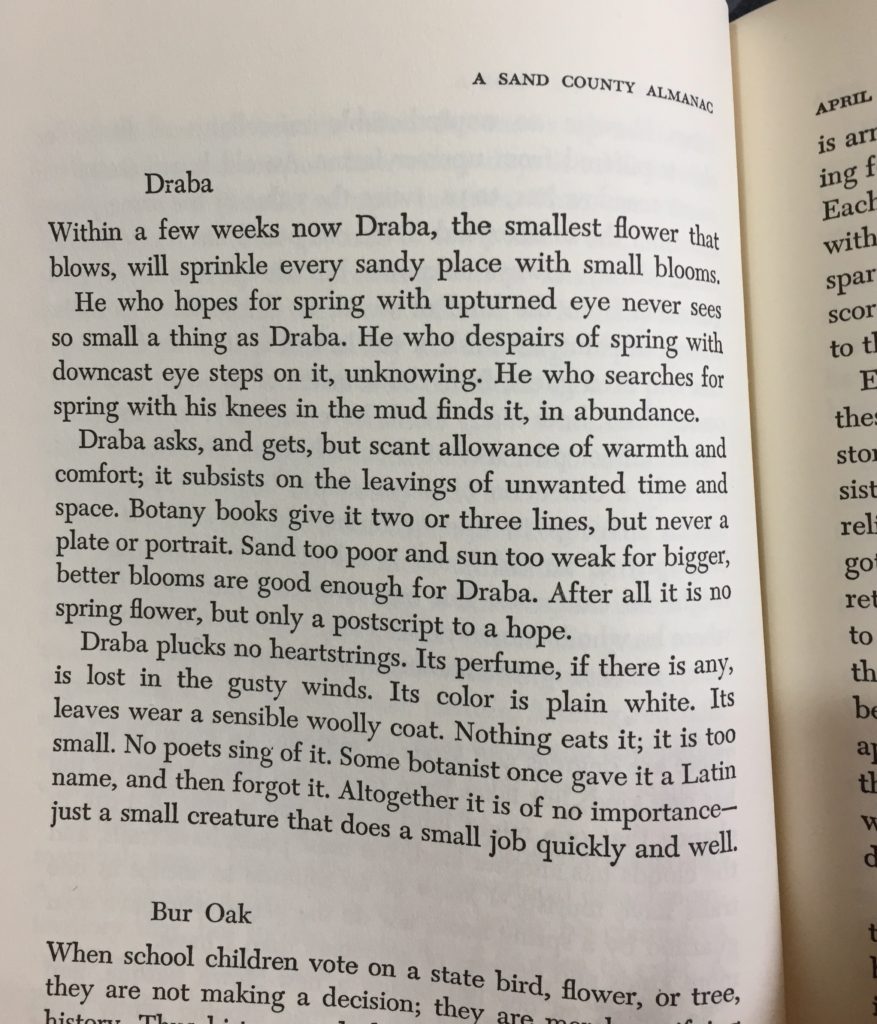

Leopold’s ode to Draba is a one-page, concise essay that re-aligns one’s focus on the beauty of early spring wildflowers–the obvious being that the plant serves as a harbinger of spring. Leopold’s main point though is more an exploration into the qualities of a person who takes notice of a flower like Draba. The choice of Draba is surprising. One would expect a more showy spring flower, like Pasque flower (in another essay) but this choice is indicative of Leopold’s genius–that even the most nondescript, overlooked part of nature has something to teach us. So much is packed into such a small piece. Like a Japanese ink painting, Leopold words create an image with sparse but well-placed words instead of brush strokes. Take a moment to read it.

Typically, when inspired by one of the essays from Sand County, I would act immediately to learn more, if the topic were unfamiliar to me. But for some reason the Draba essay just sat and smoldered in my mind. I didn’t go right out and find a specimen of Draba. I didn’t look up Draba specimens in the Herbarium at the Kansas Biological Survey. I don’t even remember looking up what the flower might look like. It is listed and there is even a photograph in my go to reference from the time, W.C. Stevens’ Kansas Wildflowers. My primary plant identification strategy in those days was using a flora with a dichotomous key–something like Flora of the Great Plains. And using a key required I have the plant in hand.

Memory is a funny thing when trying to remember your motivations from 45 years ago but I imagine I was hoping to somehow “discover” Draba on my own, without any help. I seemed to think I’d just recognize it on sight somehow, guided by the impressions formed by the essay. I kept an eye out, each spring for a little white flower that would speak to me, then I’d identify it and reconnect to Leopold’s own experiences. Each spring for forty plus years, as I wandered in fields and woods searching for spring, each new sighting of an unknown, small, weedy, white flower would reawaken the old question–Is that Draba? The answer was always: “No.” Years of not having success connecting with this plant put a damper on the quest. I began to think that if Draba was in Kansas that it must not be very common. But I never forgot the essay or the name.

Last spring, 2018, I started volunteering as a docent at the Konza Prairie–something to do in retirement. Some training is involved. One part of the training involved learning plants to expect along the nature trail. Jill Haukos presented a slideshow with photos she took herself of the prairie plants of Konza. This training was the first week of March–their off-season. Jill would show a slide and ask the docents if they knew the plant. She’d then go on and cover some pertinent information that could be useful as we led students on tours later in the spring. There was a rhythm to the presentation with slide, question, answers, follow-up. I was familiar with most if not all the photos so I thought it best for others to chime in. That changed when Jill showed a slide of a little white flower I didn’t recognize even though I’d been on the trail dozens of time during all seasons. As I was puzzling out the identification she identified it as Draba cuneifolia. “WHAT? “Draba?” “Are you sure?” “I’ve been looking for Draba for 40+ years–and it is right here?” I peppered her with all sorts of questions (probably to the distraction of the other docents.) “When does it flower?” “Where do you find it on the trail?” “Just how big is this flower?” “Have you read the Draba essay in Sand County Almanac?”

Jill is very gracious and tolerant of bio nerds since she is one herself. (that’s a compliment) She volunteered to show me a small population right outside the door that she keeps track of each year, recording the flowering time. “What?” “I’ve been walking past this plant for years and haven’t seen it?”, I repeated one more time for emphasis.

I had a difficult time sitting through the rest of the day’s program. I figured if Draba flowered at the Shack, in Wisconsin, in April back in the 1940s then there might be a chance it would be an extra early March flower in Kansas. I was like a kid on the night before Christmas, the expectation of finally seeing this flower was almost unbearable. Of course by now in my life, I’ve learned to temper such over the top anticipation with a bit of dread of being somehow disappointed. After, the meeting, we went out to see if it just happened to be up yet. We walked over to the edge of the mowed lawn where Jill normally found the plants. I got down on my knees to see if I could find it but we were unsuccessful. We couldn’t even find an early sprout. Jill, likely detected my disappointment. She volunteered to keep an eye on the plants and she’d let me know when the plants were blooming. I took her up on her offer and assured her, I’d make the hour and a half drive over to view this plant once it was in flower. Remember, I said she was gracious. She understood how an irrational passion can motivate a bio nerd.

My quest for Draba was resurrected. Disturbances in the upper atmospheric polar circulation in early 2018 led to a polar vortex dropping down into the central US. This, in turn, led to a cold February and early March. Not unlike the late winters of my youth. Naturally, this delayed the spring flowers a bit. So I found myself trying to muster some semblance of patience, waiting for Jill’s email announcing the flowering.

I was able to pass the time by researching the essay and the flower more. First, I re-read the essay and paid particular attention to the line that suggested that even a botanist would just identify the plant and move on. I searched the scientific literature to see if much had changed since Leopold penned his work. While I did find quite a few papers on the taxonomy of the group I was hoping to find papers where researchers had uncovered some story of an ecological interaction between Draba and its pollinators or the special adaptations of the plant–some story that would help me build more connections to the natural world. I did not find much although my search skills might be lacking. I did find a few papers by one lab that focused on seed germination for one species of Draba and I found that there are Draba native to North America, unlike so many of the spring mustards that show up as early weeds. I like to think that was important to Leopold as he chose the flower to focus as a sign for early spring.

On the other hand, the taxonomic papers generated a big surprise. Apparently, the genus name Draba (such an apt name for a plant so overlooked) is in the process of being replaced/restored to a prior genus name: Tomostima. I say “in process” simply because it takes a while for the plant systematists to all come on board after a revision paper has been published. This could be something of a game changer. I wondered how Leopold would have titled the essay had the genus been Tomostima in the 1940’s It also meant that any searches would need to explore both Draba and Tomostima. (I have listed some of the resources I found at the end of this piece.)

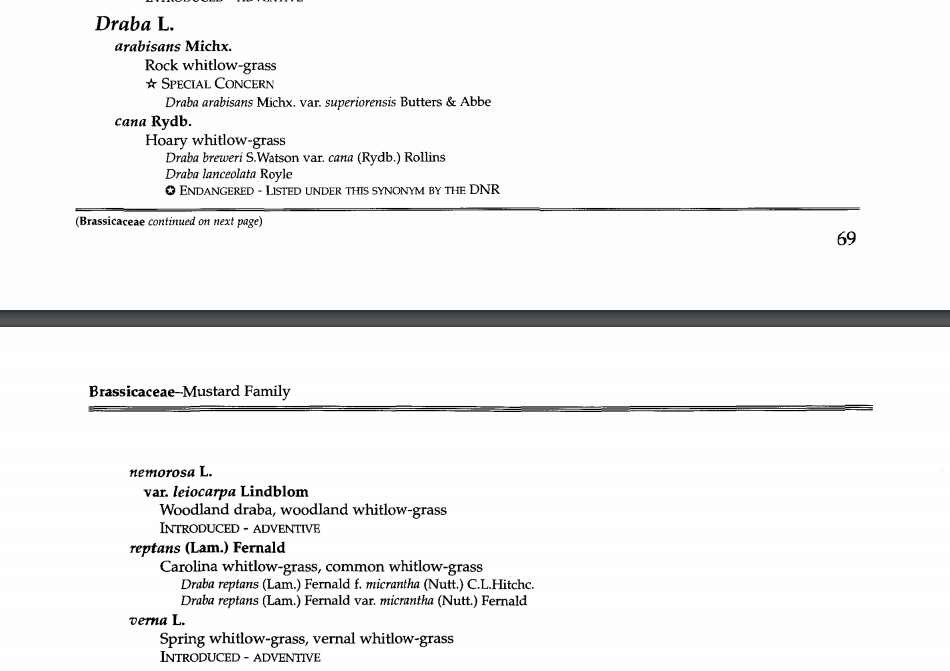

I took some time, then, to explore the University of Kansas McGregor Herbarium databases at the Kansas Biological Survey. Here, I learned that we have three main species of Draba in the state: D. cuneifolia, D. reptans, and D. brachycarpa (should have gone to the herbarium a long time ago). The majority of Kansas specimens were D. cuneifolia. D. reptans was fairly common in the collection and D. brachycarpa seemed to have the fewest records. This, of course, created an issue. Leopold had not described his Draba to species. Remember the essay was short and concise. So naturally, I did more google searching to discover the range of different Drabas in Wisconsin. I found Wisconsin has more types of Draba than we do but they apparently don’t have D. cuneifolia, our most common Draba. Here’s a screenshot from Wisconsin’s DNR’s Vascular Plant Checklist.

I looked at many range maps to try and get an idea of what Draba may have been blooming on the sand blowouts along the Wisconsin river. I narrowed it down to probably D. verna or D. reptans. I was leaning to D. reptans partly because it is a native. Turns out that D. cuneifolia and D. reptans are essentially like sister species. They are very similar in appearance and closely related. I found an excellent resource with great photos comparing D. cuneifolia and D. reptans here. Oops, except that the generic name in this resource is Tomostima. I had to remember to repeat every search with Draba and Tomostima.

I was truly enjoying the hunt and learning so much. In fact, I was beginning to develop the confidence that even if Jill’s population of Draba didn’t pan out this year, I’d be able to find it myself. Finally, on April 19th, I received an email that said: “The Draba is finally blooming.” By the way, this year’s Draba started blooming on the Konza during the first week of April so last year was really late. I gathered up my SLR, macro lens, and wide angle lens and the next day drove the hour and a half to the Konza.

Today, was the day. Almost 50 years of waiting to see this diminutive plant. Yes, it did occur to me that it was a bit crazy to get so worked up about this plant but really isn’t that part of what life is about?

Jill was waiting for me and was eager to show me the Draba near the Headquarters. I carried two lenses and my camera to record the day for posterity. I was going to get every angle of this little plant. We walked over to the edge of the lawn and Jill kept looking down. “It’s right here, somewhere,” she said. And then, “There it is, you are about to step on it.”

There it was. Such a small plant but one that begs for closer inspection. I broke out the camera gear to start taking photos. I wanted this moment captured even if the photos couldn’t capture my thoughts–they’d remind me of the day. Just one problem. I apparently forgot to check my battery. It went dead on start-up. Sometimes things work out for the best. Had I had my camera I immediately would have taken a large number of photos focusing on what the images looked like instead of paying attention to the detail of the plant itself. I had my hand lens and so I got down on the ground and took a good look at this plant. It exceeded my expectations. I don’t know what I expected–maybe some spindly thing like chickweed–but I hadn’t quite envisioned this cool little plant. From the flowers to the hairy stems to the thick rosette of leaves covered with fascinating hairs this was a very attractive plant–as long as you were down at its level.

As I used my hand lens it occurred to me that I could still take some images with the lens held up to the iPhone

I was able to get some poor photos after all to remind me of the day.

I was grateful to Jill for sharing this plant with me. I learned a lot with this first glimpse of the flower. One of the most important things I learned was that the quest wasn’t over. I hustled back to Lawrence with the knowledge that the plant was flowering, right then, in Kansas and it was time to get out and find some on my own.

From my herbarium research, I knew that some Draba had been collected at Lone Star Lake which was only about 15 minutes from my door. I went down there the next day and searched for several hours before I found a really nice population in flower and actually setting seed. And this time I had my camera battery charged.

Now that I had “my own” population of Draba to attend to I could further my explorations into this plant. I decided to see if I could find out more about the population at the Shack in Wisconsin. One of the very good things about the internet is that several libraries and museums have digitally archived records. The University of Wisconsin Madison has done that with Leopold’s papers, his field notebooks, and his journals. This is a very cool resource. I went there to see if I could find some field notes or perhaps even the first drafts of the essay. https://uwdc.library.wisc.edu/collections/aldoleopold/

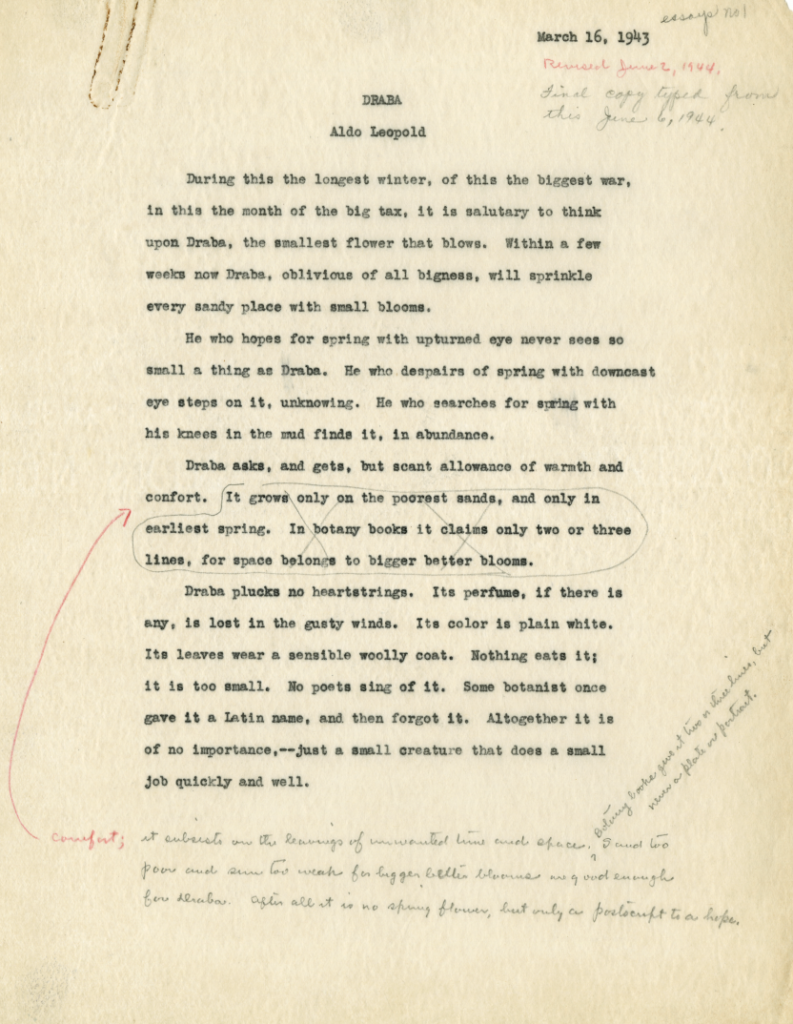

I found Leopold’s drafts of his Draba paper in this document: http://images.library.wisc.edu/AldoLeopold/EFacs/ALWritings/ALSandCounty/reference/aldoleopold.alsandcounty.i0002.pdf It takes a while to download and the Draba essay is at the beginning. This is a treasure. (edited April 18, 2019: added page image and removed description of seeking permission.)

There is so much to learn. One of the first things to note is that he first worked on a draft of this essay in March of 1943 in the midst of some of the most worrisome times of the Second World War. And typical for Leopold he let it simmer and didn’t revise it until more than a year later. (By the way in deference to the Leopold essay technique, I thought you should know I started this essay last year as well. 😉 )

Knowing this essay was penned during the war, it is not surprising that the initial draft and his final draft start with this paragraph and a reference to the war:

“During this longest winter, of this longest war, in this month of big tax, it is salutary to think upon Draba, the smallest flower that blows. Within a few weeks now, Draba, oblivious of all bigness, will sprinkle every sandy place with small blooms.”

It would seem that the focus of the essay Draba was more of a message of hope in the middle of a devastating war and perhaps not so much about the renewal of spring. This is a much more poignant message and a big surprise for me. Sand County Almanac was published after the war and after Leopold had died fighting a brush fire. His son Carl and the publishers, took to doing the final edits. I can’t find any record of why they made the decision to remove that opening paragraph. I could guess but I won’t. I feel fortunate to have found the draft and to have probed a little deeper into Leopold’s thinking and into the way he worked. Like the flower in the essay, the essay is extreme in its brevity but rich it what it tries to convey.

After reviewing the drafts I think I began to understand why Leopold titled this essay with the generic name Draba when he could have used a common name as he did in other essays. This Draba quest keeps on giving and it is not over.

For one, I needed to find out which species of Draba can be found at the Shack. I sent a Facebook message off to the Aldo Leopold Foundation.

And I received this helpful reply.

This was great. We have D. reptans and it is almost identical to D. cuneifolia. Now I could start looking for D. reptans. I’m now into my second year of looking for reptans and have yet to find it. But I have revisited many Draba at Konza and in Douglas County. I still have a week or so to find some reptans but I may have to try places other than Douglas County. I’m considering transplanting a few individual plants from some of the populations I’ve found to grow them at home in order to learn more about them. I’m going to look for populations out in the Smoky Hills around Kanopolis this weekend since the sandy soils would be ideal for D. reptans. The questions and ideas keep coming. What a great little plant. Thanks to Jill for reawakening my quest.

An update April 18, 2019:

Last weekend, Carol and I did head out to the Smoky Hills to look for Draba reptans. I’m not sure why but I had developed a search image from seeing online images and information coupled with personal knowledge of the habitat at the Leopold Shack as well as the descriptions of several of the areas where D. reptans had been collected in KS. For example, for one specimen in the herbarium collected in Ellsworth County, Craig Freeman described uplands above Alum Creek, only a mile or two from where I planned to look. I know the area very well and started to visualize the specific habitat. I thought I’d look at some of the bare, shallow soil areas that are associated with some of the sandstone outcrops along the ridge lines of the canyons. We stopped first at Mushroom Rock State Park which happens to be next to Alum Creek.

What struck us immediately was the large numbers of Spring Beauties (Claytonia virginica) in bloom along with a scattering of Carolina Anemone (Anemone caroliniana). In the mowed areas there was a carpet of Spring Beauties. It was stunning and along with the beautiful sunny weather truly started the day off right.

This park is often listed on those “Hidden Kansas Gems” websites. It has some very interesting sandstone concretions that due to differential weathering have created rock mushrooms.

Nationalparks [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)]

It is located a few miles north of Kanopolis reservoir. In addition to the standing “mushrooms” there are also a number of concretions that are just sticking out of the ground. This was where I had decided to focus my search. I looked around several of the rocks and wasn’t really finding anything–perhaps too distracted by the other more showy flowers. As I approached this rock I went into my “Where would I be if I were a D. reptans mode of thinking.

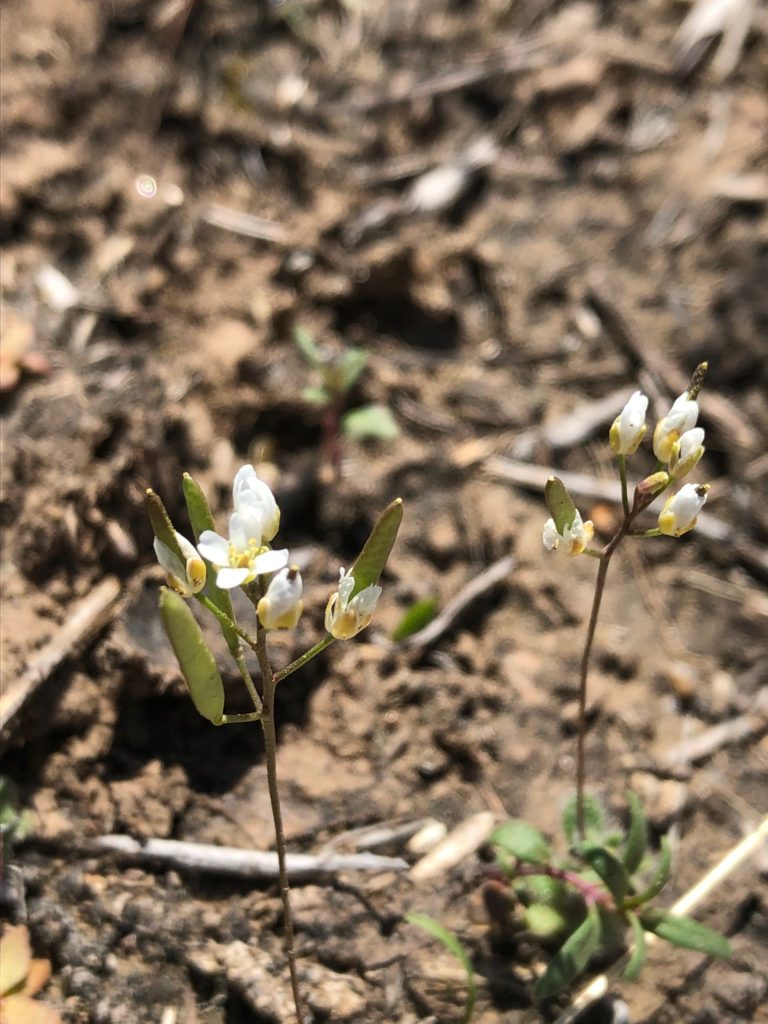

I sat down on the rock, thinking that water would run off of this surface and accumulate just a bit more at the bottom of the slope creating a slightly more moist microclimate that was also likely a bit warmer due to the rock mass gathering solar insolation. (I know, real nerdy thoughts). I was thinking that if I were a Draba reptans, I’d want to be right at that little area of bare dirt, right next to where the rock emerges from the soil. Just as that thought popped in my brain, I looked down and saw this.

Sorry, the image is a bit out of focus. It can be pretty difficult to get the entire flower in focus. But you can see that unlike the Draba cuneifolia, the pedicel is lacking hairs in the upper 2/3’s. It is also thinner. I immediately recognized it as D. reptans, although this was the first plant I had seen. I was elated. Carol took this photo of me lying down on the grass trying to get in close. What you can’t see if the big grin on my face. I had made the final connection to Leopold’s Draba

Once we found the first plant, we found many more as our search image improved. Right around the corner we found this one.

As our search image improved we noticed that cryptobiotic soil crust areas almost always had some Draba reptans.

We had a very successful trip to Mushroom Rock but had more business at Kanopolis where my sister and brother-in-law live. So we reluctantly left. Turned out my sister wasn’t home so Carol and I decided to see how many Draba we could find in Horsethief Canyon. Turns out a lot. We found Draba along the trails in the bare or crusty soils. I also found it along the margins of the rim rock in locations like this. There were several plants in the very shallow soil on the edge of the rock.

We found so many clumps along one of the trails, Carol took to calling these groups of plants “Leopold Gardens” Such a great description. There is so much irony finding this plant here. I consider these hills the center of my universe. This is where I grew up. I’ve wondered these hills for more than 60 years and yet I find new treasures every time I look. Like the Draba.

Based on conversations I’ve had with others who have a long term acquaintance with this plant this is apparently a good year. With hundreds of plants observed, I went ahead and collected a couple from the county roadside to take back to the Kansas BioSurvey to confirm my identification. Thanks to Craig Freeman for making my day. It didn’t take him but second to confirm that the plants from Ellsworth county were Draba reptans. We had a nice chat about search image and how it feels to find a plant right where you think it should be–kind of like fly fishing and throwing a dry fly in just the right spot, knowing that a trout will rise.

I’m not sure where this journey will go next but we did find more Draba at the Konza, yesterday–in fact, Leopold Gardens. It is hilarious that a plant I wanted to see for more than 50 years was now “everywhere.” I do know one thing. I’ll never have any trouble remembering the name of this plant or what it looks like. I’ll be looking for it every spring with anticipation.

minor edits on April 29, 2019

edit on April 13, 2019 to add a small bibliography for those fellow geeks (not including the original Leopold work.) These are just papers related to Draba/Tomostima.

Al-Shehbaz, Ihsan A. “A Generic and Tribal Synopsis of the Brassicaceae (Cruciferae).” Taxon 61, no. 5 (2012): 931–54.

Baskin, Jerry M., and Carol C. Baskin. “Germination Eco-Physiology of Draba Verna.” Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 97, no. 4 (1970): 209–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/2483459.

“The Light Factor in the Germination Ecology of Draba Verna.” American Journal of Botany 59, no. 7 (1972): 756–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1972.tb10149.x.

Cruden, Robert William. “Pollen-Ovule Ratios: A Conservative Indicator of Breeding Systems in Flowering Plants.” Evolution 31, no. 1 (1977): 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1977.tb00979.x.

Jordon-Thaden, Ingrid, Irina Hase, Ihsan Al-Shehbaz, and Marcus A. Koch. “Molecular Phylogeny and Systematics of the Genus Draba (Brassicaceae) and Identification of Its Most Closely Related Genera.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 55, no. 2 (May 2010): 524–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2010.02.012.

Lariviere, Andrew, Lisa B. Limeri, George A. Meindl, and M. Brian Traw. “Herbivory and Relative Growth Rates of Pieris Rapae Are Correlated with Host Constitutive Salicylic Acid and Flowering Time.” Journal of Chemical Ecology 41, no. 4 (April 1, 2015): 350–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-015-0572-z.

Mosquin, Daniel. “Constantine Rafinesque, A Flawed Genius,” n.d., 9. http://arnoldia.arboretum.harvard.edu/pdf/articles/2012-70-1-constantine-rafinesque-a-flawed-genius.pdf?